Writing

Writing your way to success

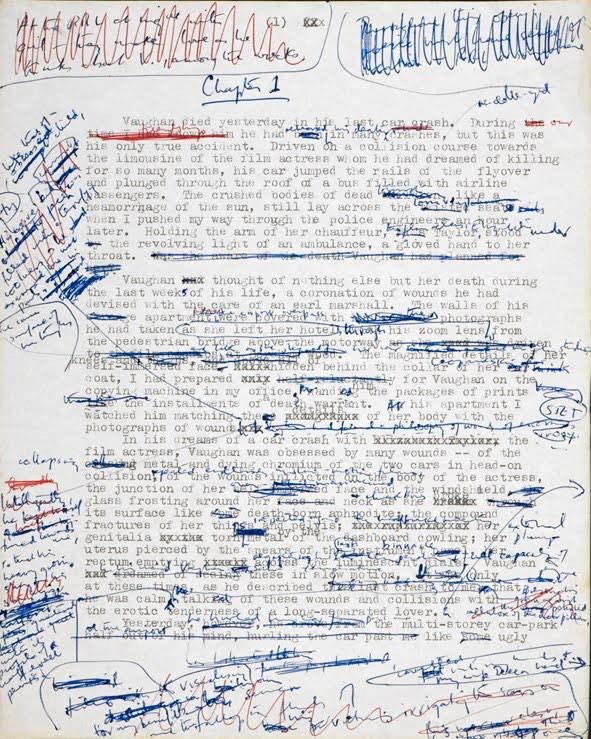

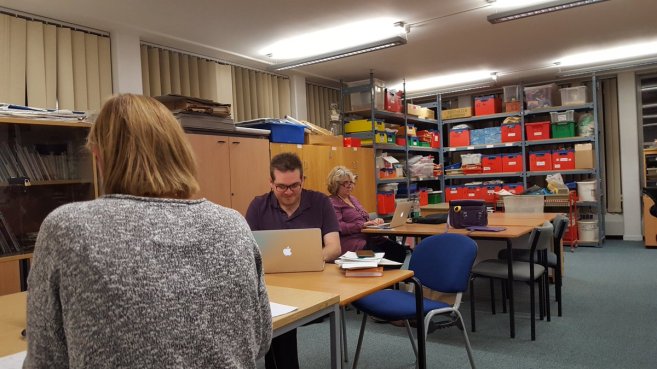

(This is a picture Lee – looking sceptical – with Jacqui and a shy Kathryn)

November 18, 2016 Lee Fallin EdD, Space

reblogged with assumed permission from here: http://leefallin.co.uk/2016/11/writing-your-way-to-success/

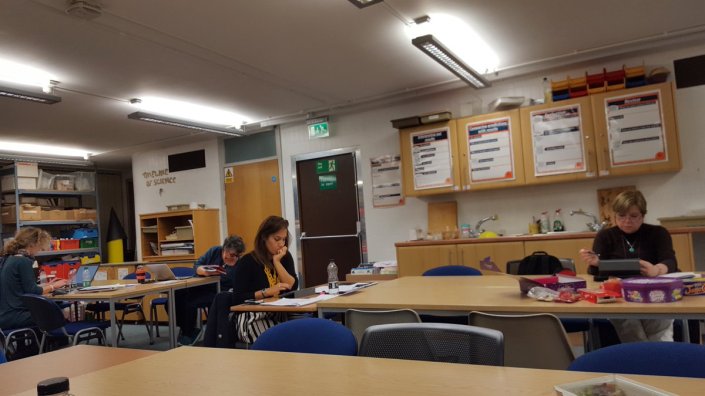

Today I took part in my first writing retreat, organised by @azumahcarol as part of the University of Hull, Doctor of Education (EdD) programme. I have to admit that while I had read some literature on support of this process (Murray & Newton, 2009; Moore, 2003; Petia & Annika, 2012), I was sceptical about it in this context. Sitting down from 9am to 5pm and focusing on writing alone sounds like a great idea – but I had two main concerns:

- The third year EdD students had not seen each other for weeks. In the case of our three Netherlands-based peers this was MONTHS. Surely after so much time apart we had too much catching-up to do to sit in silence?

- We are all at the very start of our thesis stage and sitting and writing for a whole day seemed like a big commitment and something we may not be ready for. (Okay – I admit, moving house has seriously destroyed my reading time!)

Despite my concerns, I hit the ground running this morning. I was determined to make the most of this opportunity. It isn’t often that I get such a large block of time to work on EdD coupled with the guarantee of no distractions. I had to make the most of opportunity as it was costing a day of annual leave. If I was going to waste the time, I’m sure I could have found something more fun to do.

For the first session I was able to write over 1,200 words in the 90 minute block. In honesty, most of this was achieved in the first 60 minutes as my concertation seemed to stagger towards the end of the block. I had a similar record for my second session 90 minute session, taking my total to around 2600 words. I have to admit I was proud of myself. 2600 fairly decent words in 3 hours. Just some tidying and referencing to go.

We concluded the morning at 13:00 and set off for an hour break. I was certainly hungry by this point and needed the break. I have to admit I had some concerns about the afternoon as my head was rapidly running out of things to write about. My lack of reading was finally coming to bite me.

Strategically, I spend the third session in the afternoon looking at something different. I was recently rejected from a journal and had to respond to some comments. This wasn’t my best idea as after the first 40 minutes I was thoroughly depressed and it soured the rest of the session.

That brings me to the last hour. It gave me the opportunity to Mindmap some new ideas, add another 300 words to my total and then write this.

All in all, I’ve written 3460 words today (including this blog post) and I’m pretty happy with that 🙂

Yes – I’m completely sold on structured writing days and I look forward to the next similar opportunity. We also did pretty well at resisting the temptation to write so clearly we’re all very dedicated! The power of finding ‘space’ to work.

References:

Moore, S. (2003) Writers’ retreats for academics: exploring and increasing the motivation to write. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 27(3), 333-342.

Murray, R. & Newton, M. (2009) Writing retreat as structured intervention: margin or mainstream? Higher Education Research & Development, 28(5), 541-553.

Petia, P. & Annika, C. (2012) Using structured writing retreats to support novice researchers. International Journal for Researcher Development, 3(1), 79-88.

One love. One story

A friend of mine who now teaches creative writing in a central London adult education institute – started her career as a well paid and successful actor, theatre director and writer. On one of our regular caffeination sessions sitting in what we fondly referred to as our college annexe, we talked in detail about workplace micro-politics. We called it analysis rather than gossip. The details varied from week to week but the situation was nearly always the same. We would discuss: in this particular set of circumstances what should we do, think or feel? On one of our many occasions, my writerly friend suggested that each of us only ever have one story to tell. Each of us tell our one story again and again and again. The trick, she says – is telling that story in as many different ways as is possible. I like that idea. Not least of all because it reminds me of one my favourite books. I’d like to suggest this book is a deeply influential complex paradigm shifting academic text, but it isn’t. It’s a graphic novel: 99 exercises in style.

This book takes a single story –

a man is sitting at his computer when he decides he wants to go down stairs to get something from the fridge. On his way downstairs someone (off screen) asks him the time. He looks at his watch and says it’s 1.15. He gets to the fridge, opens the door and forgets what he is looking for.

The template for this story is illustrated above.

Is it possible to tell that story 99 times? Below are two (of the 99) versions of it.

1) In one telling he focusses on only the important bits of the story – the hands and the punctuation:

2) In another the story is deconstructed and presented as an inventory of its constituent parts:

In academic writing – empirical or theoretical – we are telling one story.

It really doesn’t matter what we are writing or why. We tell, one autobiographical story. That is: I have come to understand something in a particular way. And this is why. We tell that story again and again and again in everything and anything we write. Because it is autobiographical, I can’t assume my reader knows what I know. If they do, they may not know it in the same way. I have to tell them the story of what and why I think this or that or something else.

The style may differ – that is I might choose to extract and focus on specific details. I may present the details in several different ways. I may even have distinct sub-plots that run through this story.

My colleague Claire Aitchison talks about writing the story of your research in terms of a generic Mills and Boon storyline.

That follows a pattern with its own acronym: IMRAD, introduction-methods-results-and-discussion

But of course this is just one of the 99 possiblities. The template remains the same. I now hold this view of the world and this is why. This is an autobiographical narrative that takes time as the central protagonist. Time is conceptualised as moving forward in a uniform, linear direction. One logical thing after another.

There are there ways to tell your research story – sub plots if you like, or supporting detail and perhaps a change of direction. My colleague Pat Thomson suggests a number of these based on what you feel makes your story worth telling. You have come to understand something in a particular way – but why should we believe you and if we believe you why should we care?

She suggests we may draw on a narrative that follows a slightly different structure:

Thesis to ‘proof’ – you begin with a proposition and then demonstrate its veracity by considering evidence and counter evidence.

Problem to solution – a problem or problematisation is outlined and then the steps to a ‘solution’ – or a different problematisation – are laid out. Alternative solutions are considered and reasons for rejecting them given.

Question to answer – a question is posed at the start, and justified – and the answer built up. Alternative answers are considered and dealt with along the way.

Compare and contrast – the topic is presented and the need for a comparison is given. Material which compares and contrasts is presented and lessons drawn from the exercise.

Cause and effect, or effect and cause – either the cause or effect is presented and justified. The connections are traced and evidenced. The implications of knowing the now apparent causal relationship are elaborated.

Known to unknown or unknown to known – the initial state of knowing or unknowing is outlined and a rationale given for why it is important to un/know it. The reader is led through a set of steps to the opposite condition and the So What – why we needed to do this – is explained.

Simple to complex – a simple or commonsense understanding is presented, and then a set of issues which complicate the initial situation are outlined. Reasons are offered for the importance of these more nuanced understandings.

All of these are of course different ways to tell the same story. Your story about what you now know that you didn’t know before.

Reference

Madden, Matt (2006) 99 ways to tell a story: exercises in style, London: Jonathan Cape

Writing from the margins – a few left over thoughts from (not quite a) week end 2 #HullEdD

The quote below is from something a read a while ago. It is the opening sentence of a paragraph, that has been floating around n my head for months. I have never quite found a moment to refer to it.

‘The idea of objects having a social life is a conceit I (Appadurai) coined in 1986 in a collection of essays titled The Social Life of Things. Since then, I (Appadurai) has have continued to be engaged with the idea that persons and things are not radically distinct categories, and that the transactions that surround things are invested with the properties of social relations. Thus, today’s gift is tomorrow’s commodity. Yesterday’s commodity is tomorrow’s found art object. Today’s art object is tomorrow’s junk. And yesterday’s junk is tomorrow’s heirloom.’

Appadurai, A. (2006). The thing itself. Public Culture, 18 (1), 15.

There are some things you read that for some reason capture your imagination. Perhaps they are well phrased or present an unexpected line of argument. I have not read very much of Appandurai’s work but I liked this idea of ‘things’ having a social life – dependent on the social transactions they are caught up in. I like the idea of the social life of which they are part having the capacity to transform them.

I connect this to the idea of written notes scribbled in the margins of what you are reading. These tiny little thought pieces – or perhaps conversations between you and the writer of a text – can be transformed into a paragraph and illustrated. They are of enormous value. Not only do they plot the development of your ideas from doctoral candidate to post-doctoral researcher – they represent your personal engagement with a text. They may well be junk (if treated as such), but junk if carefully collated might well of more value then you realise. More importantly, they have a name.

These are a few of my favourite …. blogs

You may use blogs to explore all sorts of idiosyncratic interests such as raindrops on roses, or whiskers on kittens if you wish. This is a legitimate use. In this post I want to offer a few of my favourite blogs that I think might be of use for Doctoral researchers. I have tried to keep this as broad as possible – given that we all come from dramatically different educational contexts.

As well as providing conversational scholarship, a blog post is a perpetually open text, we can add, delete or change the history of the blog at will. With the blog time is always being re-written. If I note other useful blogs that I think colleagues may like, I shall edit them in … or write a new post.

So – for starters – these are my favourite blogs that I think you might enjoy:

https://patthomson.wordpress.com/author/patthomson/

This blog offers advice and guidance about academic writing. Anything from writing field notes, to writing on a day-to-day basis for your Doctoral Research. I quite like reading about the big themes of academic writing as well as the mundane details of academic practice. Pat’s blog gets the balance right in my view – between autobiography and analysis. Lots of really useful advice.

http://sociologicalimagination.org/archives/author/markcarriganauthor

Mark’s blog might not be for everyone. But, although he has only just completed his PhD he has a very well established reputation in how academics can use social media. He is also a sociologist. This is my disciplinary home so I admit to being biased. He’s not for everyone and writes very little about education. But for everything else social theory – this is the go to blog for inspiration. He also offers an excellent account of academic blogging.

Eddie is the principal of a 6th form college, I include his blog as an example of an established professional with an institutional reputation to defend. The blog offers more the PR and represents his broad view on the world. In this post, he is politely political without compromise to either is personal or professional integrity.

Andrew blogs about his research. He’s a prolific writer whose focus is on good governance in schools. This is his official blog that traces the unfolding of his ERSC funded research project School Accountability and Stakeholder Education (SASE) from its inception in 2012 to its conclusion on February 2015. He’s not a light read but for the school based researchers, he’s very interesting. This is a great example of blogging while researching.